Tunnels and Bridges, oh my

Originally published on medium.com

Part I of a series looking at the current state of multi-chain DeFi and blockchain interoperability

This is my attempt to explain what is currently happening with so-called “bridges” — i.e. the systems to move assets between settlement layers on a blockchain and between blockchain.

If you are new to what an “L2” (or layer-2 e.g. scaling solution) is, as always, the very thoughtful Vitalik has written something that should get you from 0–60 very quickly…this was very helpful to me: An Incomplete Guide to Rollups. For those coming from traditional financial services…a rollup or L2 scaling solution is simply netting transactions, and then settling those transactions back to the underlying blockchain (say, Ethereum) on some regular interval.

There are many functional, structural, and security trade-offs that prevail; for what we are talking about today, I think it’s safe to assume that 1) there will be many blockchain confirmation venues both as blockchain and scaling solutions, 2) many of them will be ETH-based (“EVM-compatible”), and 3) no one really knows where this will actually wind up, so if it seems a bit complex and confusing, that’s A-OK.

For folks who followed the installation of the internet: the parable that I give is that we are in the moment when people might say “who needs the internet, there are already 5 phone lines connecting the Berkeley and Stanford Campus networks!” This of course assumes that 1) the only people computing will be at these “hub” networks and 2) a 1:1 linkage is all that’s needed. TCP/IP and generalized “routing” is coming to crypto. It’s not built yet. It could be messy. There could be many competing standards since value is…well…more valuable than information: different transactions will be willing to have different tradeoffs, vs a world where the internet pipes just got wider and the old protocols scaled with more information.

Multi-chain namespaces

While likely incomplete, many different projects use somewhat ambiguous terms to describe what exactly they are bridging to where.

My attempt here is to:

- Define standardizing language to describe the different fund flows, and

- Segment the real bridge usage into a few different categories

First off: now that assets can exist on different blockchains than they came from, we are going to adopt the same language that the Thorchain team has created, as a leading project in multi-chain defi. (We’ll talk a lot more about Thorchain later.)

This is describing assets as follows:

Thus, Matic.USDC would be ERC-20 USDC living on the Polygon Matic Chain. Or SPL token USDC on Solana would be SOL.USDC. This is important particularly when we start moving the same asset between chains: e.g. porting mainnet ETH (ETH.ETH) to the Arbitrum scaling solution (Arbitrum.ETH).

Three primary bridge cases

So with that out of the way, let’s have a look at the three core uses of bridging between different blockchain settlement networks:

- Today: Movement of assets. Asset A on Chain A [e.g. ETH.ETH] → Asset A on Chain [e.g. MATIC.ETH]

- Part II: Exchange of assets. Asset A on Chain A [e.g. ETH.USDC] →Asset B on Chain B [BNB.BTC]

- Part III: Propagation of information. Event A on Chain A [e.g. Ampleforth rebase increases supply by 1%] →Event A’ on Chain B [e.g. AVAX.AMPL also increases in supply by 1%]

In theory, any one of these use cases is simple. Reality is far messier — 1) finding the shortest route itself is hard, 2) knowing that the path you choose is economically safe (e.g. your funds won’t be stolen by a bad actor in route), and 3) knowing that you are getting “best execution” or somewhere near that for your movement/exchange/info transfer.

Movement of assets [Chain A → Chain B]

To transfer an asset (Asset A) from one blockchain to another is in many ways the simplest use of a bridge. Earliest bridges were often built by the projects themselves — for example, Arbitrum offers a way to port assets living on ETH mainnet to the Arbitrum scaling solution environment.

But depending on the destination chain, there can be significant friction. To stay with Arbitrum, for example: it’s very simple to send ETH.ETH to Arbitrum.ETH. Just send a mainnet ETH transaction, and approximately 5 minutes later, your ETH will be available within the rollup. Going the other direction, however, isn’t such a simple proposition: withdrawals take approximately 7 days.

There’s a good reason for this: the Arbitrum transaction netting platform needs ample time for stewards of the network to detect and stop fraud from the platform — before unlocking precious ETH.ETH to a would-be withdrawal. (You can read more about this in Uniswap’s helpful article on withdrawals.)

Just this one simple example (Arbitrum.ETH -> ETH.ETH) introduces a need for more market infrastructure: speed.

How can you move faster than the 7 day accounting window that Arbitrum requires?

Simply by finding a counterparty who has both Arbitrum.ETH and ETH.ETH and is willing to accept your Arbitrum.ETH in exchange for mainnet ETH…but this comes at a fee.

Fortunately, DeFi primitives (which I’ve written about at length in my prior DeFi 101 piece) can be used to easily build a marketplace (pool) for liquidity providers who wish to offer this service.

Hop is, to my knowledge, one of the first liquidity pools (Uniswap fork) built to cater to the cross-rollup use case:

Under the hood, the Hop protocol maintains liquidity pools with equal measures of each source/destination asset pair. At time of writing, this amounted to $18m of ETH in the ETH.ETH<>Arbitrum.ETH pool.

Other techniques are emerging as well. For example, the team behind the UMA protocol (one of the early DeFi bluechips) launched the Across Protocol, powered by UMA’s “optimistic oracle.” Basically, rather than having to maintain separate liquidity pools for each Chain A <> Chain B pair, liquidity providers can simply bond a given asset (e.g. ETH) that is reused across every chain destination.

This asset acts as a bond; should a end user transfer an asset (e.g. Arbitrum.ETH -> ETH.ETH in our earlier example) and fail to receive ETH.ETH, they simple create a dispute. This goes to UMA governance token holders who would slash the bond of the LP, making the end user whole. So rather than funds being duplicated across pairs, the protocol simply requires sufficient funds in escrow — enabling even lower total costs and faster confirmation times.

These are just two example pathways on one simple bridging pair. There will always be a shorter tail of more liquid pairs, but here we have only considered one simple pair. It’s not that simple in practice, now that many different smart contract platforms have reached very material sums of assets deployed in theirDeFi protocols.

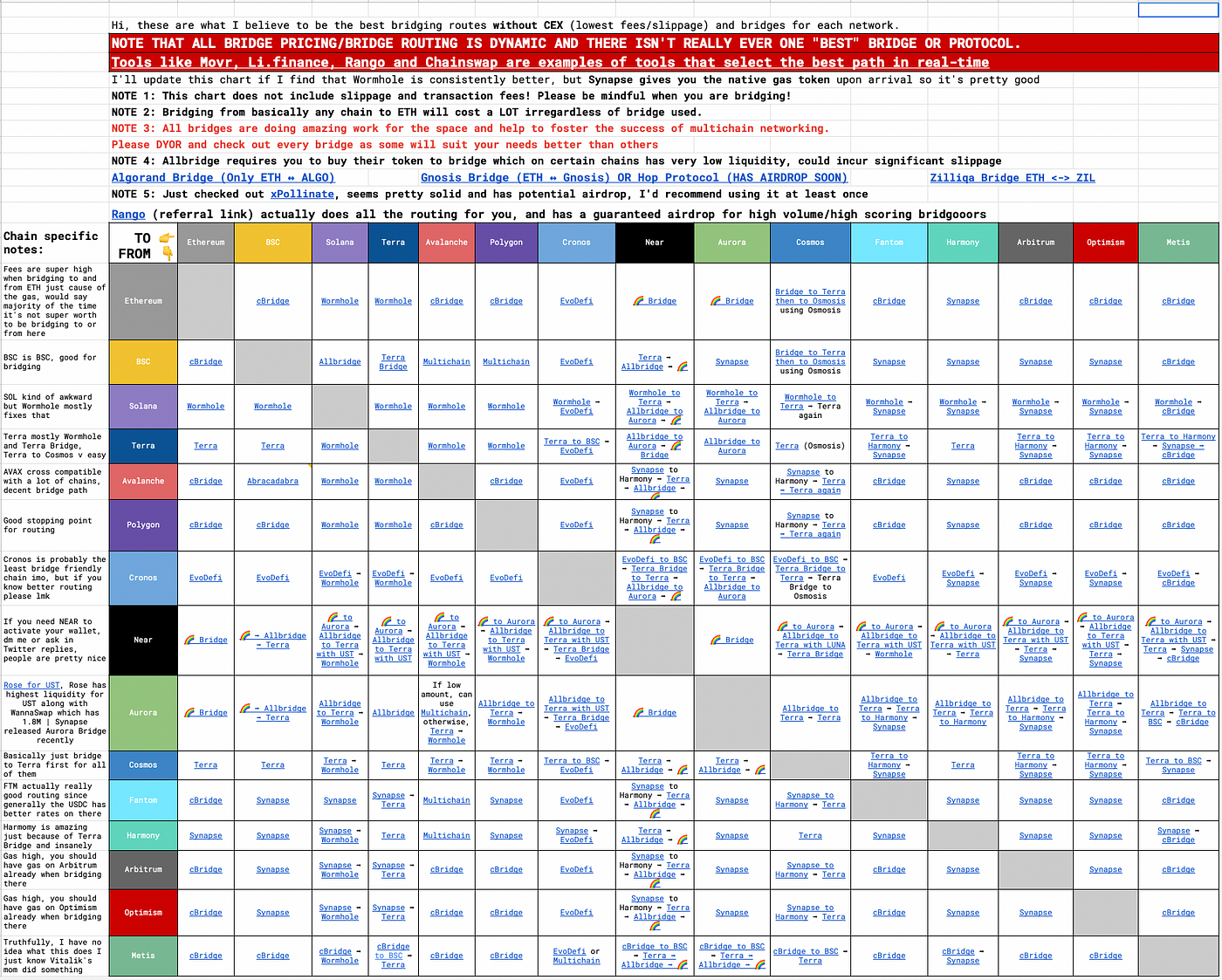

The complexity here unfortunately scales O(n²) or worse as more rollups and EVM compatible chains emerge and the number of material digital assets scale. This is just a glimpse of some of the current state:

Bridgooooooors community spreadsheet compiled by Kuro Kuro.

To deal with some of the complexity (image above), protocols like Rango are building a meta routing layer on top of underlying bridge (and exchange) liquidity. Beyond EVM-compatible bridging, we start to look at how to connect many different chains — that may not all have assets directly bridgable between them. Which brings us to the next major use case of bridges…

To be continued in Part II…

—

Have other interesting data that should be included here or further suggestions? Things you’d like to see specifically addressed in the series. Please drop me a note on Twitter @njess.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. Author and related entities may hold digital assets or equity in related businesses mentioned.